Jacqueline Winspear is a favourite author of mine. Her Maisie Dobbs series of books are excellent and although they are often categorised as crime or mystery novels all of them are historically accurate and contain perceptive insights into human nature and the lingering psychological results of war. Jacqueline has recently started a Maisie Dobbs blog that includes items on women's history and I was particularly interested in her discovery of Louise Mack, the Australian writer who is credited with being the first female war correspondent of World War I and who wrote a book about her experiences.

Not knowing anything about Louise either, I went in search of her and tracked down the biography written by her niece, Nancy Phelan, The Romantic Lives of Louise Mack.

Google Books calls this book "fictional" and perhaps it is as much of Louise's life remains a mystery and Nancy draws mainly on family memories and her own personal recollections of her aunt to round it out.

The book does succeed in an intimate look at a woman full of flaws and contradictions and who was determined to live a Bohemian existence as a free spirit. This naturally resulted in difficulties for many of those whose lives crossed with hers. Her first husband, John Creed, totally gave up drink in order to win her but when her writing career became more important than her marriage, he tragically defaulted and died a broken man. Likewise, Louise's youthful exuberant and close association with another Australian writer, Ethel Turner, fell on hard times. Yet Louise's unswerving attention and devotion to her second, much younger, husband Allan Leyland who was gassed in the First World War couldn't be faulted.

Ethel followed a more conservative life and is still well-known to many Australians due to her classic book Seven Little Australians, but Louise seems to have been completely forgotten.

She was often her own worst enemy and many times came close to starving and penury, being forced to write serials and romantic potboilers under various aliases to earn a living and she never quite reached her potential as a serious author. Perhaps one of her greatest sins was in using real characters in her books and not bothering to disguise family, friends and the socialites and other prominent individuals whom she hijacked. She was for a time the "agony aunt" at the Australian Women's Weekly and Nancy Phelan wickedly suggests she was also the author of many of the letters sent in and the "advice" given was often at odds with the morals and standards of the day and more in keeping with her own somewhat haphazard attitude to life and her neglected family relationships. Needless to say, she didn't last long in the position. Also when she travelled and lectured widely later in life, Nancy says she tended to fantasy when it came to her war experiences as well as the famous people she may (or may not) have known and thus couldn't be completely trusted.

An obituary of Louise Mack can be read here. Although she didn't have descendants, at one time she stated that she did have a living child. Nancy Phelan's book explores the possibility that there was a child born in Italy during one of her aunt's long "disappearances" but proved inconclusive.

Links to some of Louise's books including her most famous A Woman's Experiences in the Great War are available through the Internet Archive.

In keeping with her family's tradition (Louise's sister Amy Mack was also a writer) Nancy Phelan herself was equally talented and colourful individual, a winner of the Patrick White Award. Only when I read her obituary from 2008 did I realise I'd failed to notice that she was the co-author of the most reliable Russian Cookbook that has been a staple of my recipe collection for many years.

"History is a commentary on the various and continuing incapabilities of men. What is history? History is women following behind with the bucket." [Mrs Lintott, "The History Boys" by Alan Bennett]

Saturday, December 24, 2011

Sunday, November 27, 2011

The Lost Princess

|

| Engraving by E. Graves after F. Winterhalter, 1858 |

In my quest to discover the lesser-known or unusual goddaughters of Queen Victoria, I have read about the five daughters of Maharajah Duleep Singh all of whom seem to have been afflicted by the infamous curse of the Koh-in-Noor diamond (a convoluted and lengthy tale!) but in the process I also came across a recent book by Indian author, C P Belliappa, entitled Victoria Gowramma: The Lost Princess of Coorg, who was the first of the Queen's Indian goddaughters to be baptised and later confirmed as a Christian.

Apparently the Queen had hoped to marry the Princess off to Duleep Singh, but the match did not eventuate as Duleep had his eye elsewhere. Instead, she married a much older British soldier, Lt. Col. John Campbell, had one child and then died very young aged about 23 in 1864. She is buried at Brompton Cemetery in London.

More about the book and the Princess can be read in this article from The Hindu here and also this review.

|

| Frontispiece, Lady Login's Recollections |

Lady Login's Recollections about court and camp life are also worth reading as it covers in some detail the guardianship, encounter with Duleep Singh, and marriage of Princess Victoria Gauramma [sic. Gauramina] to Lady Login's brother, John Campbell, and also gives some information on her daughter, Edith Victoria Gauramma Campbell, born in London in 1861 and who became the subject of a court case over guardianship after her father disappeared in mysterious circumstances.

Lady Login's description of this oddly dressed and lonely orphan at the age of 7 or 8 being unable to read or write properly, simply known as "Gip" or "Gipsey" and who never had any friends apart from a page boy, make for poignant reading. She had no idea who Queen Victoria was and their first encounter shows that the Queen was very kind towards her and much enjoyed meeting the guileless child.

Edith Victoria married Henry Edward Yardley in Kent in 1882. According to Mr Belliappa, some of her descendants may have eventually made their way to Australia.Go to Internet Archive for this complete book.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

The Queen's goddaughter who swapped her debutante gown for a boiler suit

One notable thing about Queen Victoria's goddaughters is that they were usually - and obviously! - called Victoria Alexandrina. Godsons were variations of Alexander, Albert and Victor.

Victoria Alexandrina Drummond might have preferred Victor Albert if she'd had the choice, given her future career as the first fully-qualified female Marine Engineer. Summaries of her amazing life at sea can be found in various online links and also in the extensive article from The Daily Mail of 22 April, 2006 included at the end of this post.

Also, Cherry Drummond (Baroness Strange) wrote a biography about her enterprising aunt which was published on the centenary of Drummond's birth in 1994: The Remarkable Life of Victoria Drummond, Marine Engineer

Some of these sources state that Victoria is commemorated by The Victoria Drummond Award, the highest honour given to women members of NUMAST, the marine officers union, for work in raising the status of women members of the marine industry. However, NUMAST was absorbed into Nautilus International about five years ago and I can find no recent recipients of this award listed or otherwise easy to access and I would be interested to find out if it is still in operation.

My cousin Edward Kirton, a retired Chartered Marine Engineer, has offered the following extra information:

The Daily Mail (London, England) , April 22, 2006

Byline: KATE GINN

GIRL'S OWN GIRL'S OWN

She was the Queen's goddaughter,raised in a Scottish castle to a life of privilege.But Victoria Drummond dreamed of travelling and shocked 1920s society by training to be an engineer,joining the Merchant Navy and winning medals for her wartime feats of courage

OUT in open water and completely alone, the ship was a sitting duck. As the German bomber swooped in low, poised to attack, the crew on board the SS Bonita knew there was little chance of survival if they took a direct hit.

Were it not for the extraordinarily brave actions of the Second Engineer, they might never have made it to tell the tale. It was that engineer who, deep in the bowels of the vessel, singlehandedly kept the engines running during the heavy bombardment, enabling the ship to dodge the shells and gunfire that pounded down for more than half an hour.

Thanks in no small part to this outstanding effort, not one of the 25 bombs found their target. Little wonder that the courageous seaman of the engine room was given a hero's welcome and made headlines around the world.

But what really captured people's imagination was not so much the tale of extreme bravery but the fact that the engineer in question was a woman. Not just that, but she was upper-class and a former debutante from one of Scotland's oldest families.

How Victoria Drummond ended up spending her life in a dirty engine room doing a job so physically gruelling that most men would struggle is a fascinating story. As her niece, Baroness Strange, once remarked: 'She was a wonderful woman. My family thought she was unusual but they were very proud of her.'

Victoria was born into privileged circumstances and with Royal connections - she was christened with the name of her godmother, QueenVictoria - and spent her childhood living in a Scottish castle.

She set her heart on going to sea - a career unheard of for a lady in the 1920s.

Yet, against all the odds, she not only succeeded in becoming the first woman to qualify as an engineer in the Merchant Navy but won the respect of her male peers.

In 40 years at sea, she completed 49 voyages, circumnavigating the world many times over. Her colourful exploits could have come straight from the pages of a Boy's Own adventure book.

SHE would survive travelling through minefields with Atlantic convoys during the Second World War, was involved in the sea rescue of British forces in Marseille, risked her life to save refugees and witnessed some of the most memorable episodes of her time, including Hitler's march into Vienna and the rise of Communism in China.

Her devotion to duty would be honoured with a MBE and she was awarded the Lloyd's War Medal, presented for exceptional gallantry at sea in time of war and never before won by a woman. Incredibly, she would continue sailing into her 60s.

Her remarkable story, retold in the new Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, is inspirational.

Hers was a very traditional upbringing. Home was Megginch Castle, the 15th-century family seat in Errol, Perthshire.

The sea was in her blood. Her great-grandfather was Admiral Sir Adam Crummond, while her great-great-uncle, Robert Drummond, was a captain in the East India Company.

From a young age, Victoria nurtured a somewhat unfeminine fascination with the workings of machinery. At playtime, the little girl with pigtails would slip off to the nearby blacksmith's forge and watch as the horses were shod and agricultural machinery fixed.

One day, she summoned up the courage to ask the owner of the local engineering firm how she could learn to be an engineer and go to sea. He replied that she would have to serve an apprenticeship.

' He smiled at me in my holland pinafore and pink sunbonnet and I don't think he believed for a moment that I meant what I said,' she would later write in her diary.

At 18, she made her society debut in London, dressed in a floaty, white dress. But she was more comfortable in a dirty boiler-suit and tinkering around with machines.

When she turned 21, on October 14, 1915, her father told his daughter: 'Now you are old enough to chose a career.' She would recall: 'I told him that I wanted to be a marine engineer but I don't think he took me seriously'.

Despite her parents' reservations, she landed a week's trial at the Northern Garage in Perth. It was quite a sight to see the goddaughter of Queen Victoria dressed in overalls, scraping oil and grease from gearboxes. At the end of the week, she was offered an apprenticeship for the princely sum of three shillings a week.

Three times a week, she studied maths and engineering with a tutor from Dundee Technical College.

Work at the garage was hard, backbreaking and could be dangerous. One of the worst accidents left her nursing a broken collarbone and ribs after she was crushed by a ten-ton lorry when it slipped as she worked underneath it.

YET she was determined to succeed and eventually moved to Dundee, working in the Caledon Ship Works, as the only woman among 3,000 men. Her workmates gradually got used to the idea of having a woman working with them and, in 1920, she finished her apprenticeship, top of her group.

It took another two years before she would achieve her dream of going to sea, when she was offered the post of tenth engineer with the Blue Funnel Line, sailing from Glasgow to Australia for [pounds sterling]10 a month. In her memoirs, she describes the 'thrill' of being measured for her first uniform, with the shiny gilt buttons, epaulettes and company badge on the cap.

Before she left, her father told her: 'A good voyage, Vicky. Write home from every port and go to church when you can. You have been brought up to know what is right, so do it.'

Hours were spent in the engine room, amid the hiss and roar of the boilers and the overpowering stench of thick, sulphur-smelling steam. In a man's world, there was no place for femininity. Her hair was cut short and her fingernails were more often than not caked black with grime.

Despite the toil - often working from 7am to 5pm, seven days a week - and the grim, cramped conditions during four months at sea, she loved it. In all, she made four voyages on the Australian run with the SS Anchises and one to China.

She was in Singapore in June 1924 when a telegram arrived, breaking the news that her father had died of pneumonia. The message ended: 'He was so proud of you.' On the Anchises, Miss Drummond had struck up an affectionate friendship with her second engineer, whom she refers to in her diary formally as Mr Quayle. On board, however, they gave each other nicknames. She called him Hedgehog, because of his sometimes prickly manner, and he called her Kate, because of her shrewish manner.

Her diary leaves little doubt that she was in love with him. When their last voyage came to an end, she was distraught at the thought of never seeing him again.

'I did not want to go on sailing without my dear Second constantly to supervise, advise and protect me,' she wrote.

'Although we came from different backgrounds, our minds were perfectly attuned: we loved birds, the sea, engines and the British Empire. We shared the same wry sense of humour, the same love of travel. If there had been no Mrs Quayle, it is possible our relationship would have ripened into romance.'

She and Mr Quayle continued to correspond, on different ships and often on the other side of the world. She was at sea when she heard her beloved Hedgehog had died from pneumonia on the way to Cape Town in April 1927.

THE news left her devastated: 'I could not believe I would never see him again. It just knocked the bottom out of things for me and my whole career felt like a collapsing pack of cards. Everything in the engines reminded me of him, every tool, every job, it was almost more than I could stick.' She would never marry or have children. Determined to get on, she sat the second engineer's qualification and passed at the third attempt. By her next sailing, on the TSS Mulbera to East Africa, she had worked her way up to fifth engineer.

Yet, despite taking the chief engineer's exam 37 times, she failed each time and became convinced it was because of her sex: 'They would not pass me because I was a woman.' When war broke out in 1939, she fought against prejudice: 'No one would have me. They might be short-staffed, but that was no reason to employ a woman engineer. And certainly not in wartime.'

Eventually, she had to sign on as second engineer with a small international ship, sailing under a foreign flag. In wartime, crossing the seas was a perilous business with minefields, torpedo attacks and the constant threat of the German Luftwaffe.

She describes one particularly fierce night of bombardment, with gunfire and mines exploding all around: 'The ship was in a complete blackout and every now and then there would be a fantastic bang, which shook the whole ship. I kept thinking, "The next one will be us."' On one run, taking refugees from Gibraltar to Casablanca, she stood on deck and watched a ship sink in two minutes after striking a mine in front of them.

While she would earn the respect of her men, the British naval establishment-found it harder to accept her. On one Navy inspection, she wrote of how the officers saw her and 'looked amazed and disgusted.

I could almost hear them thinking: "Fancy having a woman Second, you can see it's a foreign ship." I was rather amused.' On August 25, 1940, after leaving Cornwall on the SS Bonita, the ship came under attack from a German bomber. Below deck, it was down to Miss Drummond to keep the engines going.

She would recall: 'I realised our only hope of survival was to dodge the bombs, so I gave her all the speed she could. I counted eight separate bursts of firing from the guns and bombs. All the lagging came off the pipes and fell like snow.

The feeling was as if the ship were lifted up and dropped each time.

'With the bombs, the machinegun fire and the engines of the plane, the noise was terrific. Flying debris hit the main water service pipe to the main engine and scalding water began to gush out. I had my ears stuffed with cotton wool to deaden the noise. There were no captain's orders. We were on our own.' Ordering her men to leave to safety, she remained alone in the engine room: 'The engine was a hissing, bubbling inferno and everything that could shake or bang rattled like marbles in a drum. The ship must be doomed.

I knew that now.

MY duty was to keep the engines going as long as they would turn. Was this the end, I wondered, banged and buffeted in the inferno of noise and steam?

It didn't seem a good way to go.' Through sheer determination, she managed to coax 12.5 knots out of the engines, a speed never before recorded in all the ship's 18 years.

Her efforts undoubtedly saved the ship and crew. Back on dry land, the brave engineer was met by journalists and cheering crowds. The ship's mate would describe her as 'about the most courageous woman I ever saw'.

After the war, Miss Drummond was on the first ship into Kiel and escorted the German prize ships over to the Forth. Bursting with pride, she wore her full Merchant Navy uniform in the Victory Parade. Of her two honours, she said: 'I was immensely proud of both my medals. They reassured me that at least someone believed my work was worthwhile.' She would continue sailing into her early 60s - taking her henna shampoo on every voyage to maintain her hair colour. And in 1959 she went through the Suez Canal as chief engineer, having at last attained the rank she had wished for all her life.

Her last voyage was in 1962 to Hong Kong. In later life, the highlight of her year was going to the Institute of Marine Engineers in London for their annual meetings.

Few knew the identity of the old lady at the back, listening avidly to all the lectures. She would have been thrilled to know the institute would later name a Victoria Drummond Room in her honour.

Her last six years were spent at a rest home in Kent. Gradually, she became more and more frail and stopped telling the stories of her time at sea. She died on Christmas Day, 1980 [sic], aged 86, leaving her unfinished memoirs. Her niece, Baroness Strange, would turn them into a book about her aunt.

Baroness Strange, who saw her aunt a week before she died, wrote: 'Victoria Drummond was finally Finished with Engines. Or perhaps as her spirit left the land and floated out to the open sea, she was at last Full Away.'

KATE GINN

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2006 Solo Syndication Limited. The Daily Mail.

Victoria Alexandrina Drummond might have preferred Victor Albert if she'd had the choice, given her future career as the first fully-qualified female Marine Engineer. Summaries of her amazing life at sea can be found in various online links and also in the extensive article from The Daily Mail of 22 April, 2006 included at the end of this post.

Also, Cherry Drummond (Baroness Strange) wrote a biography about her enterprising aunt which was published on the centenary of Drummond's birth in 1994: The Remarkable Life of Victoria Drummond, Marine Engineer

Some of these sources state that Victoria is commemorated by The Victoria Drummond Award, the highest honour given to women members of NUMAST, the marine officers union, for work in raising the status of women members of the marine industry. However, NUMAST was absorbed into Nautilus International about five years ago and I can find no recent recipients of this award listed or otherwise easy to access and I would be interested to find out if it is still in operation.

My cousin Edward Kirton, a retired Chartered Marine Engineer, has offered the following extra information:

In the early 1950's - perhaps 1953, whilst serving my apprenticeship at D.R. Dowson's & Co, Ship Repairers & Engineers, East Side, Tyne Dock, I recall one of the old hands saying that Victoria Drummond was the Chief Engineer (CE) on a Turret Ship then loading coal in Tyne Dock. The ship must have been under foreign flag for much to her annoyance she never did sail as CE under the Red Duster.Also I remember attending a meeting in the Institue of Marine Engineers Memorial Building in London, in about 1965, and recall Victoria being in the audience, but I never met her. She was a regular attendant at London meetings by all accounts since she lived in London at Kennington Road.

Sadly, it seems Victoria's twilight years were not pleasant and she was looked after by her two faithful sisters, who found her to be a trial. After becoming ill Victoria was taken to St. Thomas's Hospital, but her two sisters also became ill and died within two days of each other in the same Hospital. With her mind gone, Victoria was transferred to special care in Kent, where she spent the last years of her life gradually becoming more frail and silent. She died in 1978 (erroneously 1980 in some references) and is buried at Megginch.

More about Victoria Drummond here:

and photo of the the Drummond family graveyard at Megginch Castle

Byline: KATE GINN

GIRL'S OWN GIRL'S OWN

She was the Queen's goddaughter,raised in a Scottish castle to a life of privilege.But Victoria Drummond dreamed of travelling and shocked 1920s society by training to be an engineer,joining the Merchant Navy and winning medals for her wartime feats of courage

OUT in open water and completely alone, the ship was a sitting duck. As the German bomber swooped in low, poised to attack, the crew on board the SS Bonita knew there was little chance of survival if they took a direct hit.

Were it not for the extraordinarily brave actions of the Second Engineer, they might never have made it to tell the tale. It was that engineer who, deep in the bowels of the vessel, singlehandedly kept the engines running during the heavy bombardment, enabling the ship to dodge the shells and gunfire that pounded down for more than half an hour.

Thanks in no small part to this outstanding effort, not one of the 25 bombs found their target. Little wonder that the courageous seaman of the engine room was given a hero's welcome and made headlines around the world.

But what really captured people's imagination was not so much the tale of extreme bravery but the fact that the engineer in question was a woman. Not just that, but she was upper-class and a former debutante from one of Scotland's oldest families.

How Victoria Drummond ended up spending her life in a dirty engine room doing a job so physically gruelling that most men would struggle is a fascinating story. As her niece, Baroness Strange, once remarked: 'She was a wonderful woman. My family thought she was unusual but they were very proud of her.'

Victoria was born into privileged circumstances and with Royal connections - she was christened with the name of her godmother, QueenVictoria - and spent her childhood living in a Scottish castle.

She set her heart on going to sea - a career unheard of for a lady in the 1920s.

Yet, against all the odds, she not only succeeded in becoming the first woman to qualify as an engineer in the Merchant Navy but won the respect of her male peers.

In 40 years at sea, she completed 49 voyages, circumnavigating the world many times over. Her colourful exploits could have come straight from the pages of a Boy's Own adventure book.

SHE would survive travelling through minefields with Atlantic convoys during the Second World War, was involved in the sea rescue of British forces in Marseille, risked her life to save refugees and witnessed some of the most memorable episodes of her time, including Hitler's march into Vienna and the rise of Communism in China.

Her devotion to duty would be honoured with a MBE and she was awarded the Lloyd's War Medal, presented for exceptional gallantry at sea in time of war and never before won by a woman. Incredibly, she would continue sailing into her 60s.

Her remarkable story, retold in the new Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, is inspirational.

Hers was a very traditional upbringing. Home was Megginch Castle, the 15th-century family seat in Errol, Perthshire.

The sea was in her blood. Her great-grandfather was Admiral Sir Adam Crummond, while her great-great-uncle, Robert Drummond, was a captain in the East India Company.

From a young age, Victoria nurtured a somewhat unfeminine fascination with the workings of machinery. At playtime, the little girl with pigtails would slip off to the nearby blacksmith's forge and watch as the horses were shod and agricultural machinery fixed.

One day, she summoned up the courage to ask the owner of the local engineering firm how she could learn to be an engineer and go to sea. He replied that she would have to serve an apprenticeship.

' He smiled at me in my holland pinafore and pink sunbonnet and I don't think he believed for a moment that I meant what I said,' she would later write in her diary.

At 18, she made her society debut in London, dressed in a floaty, white dress. But she was more comfortable in a dirty boiler-suit and tinkering around with machines.

When she turned 21, on October 14, 1915, her father told his daughter: 'Now you are old enough to chose a career.' She would recall: 'I told him that I wanted to be a marine engineer but I don't think he took me seriously'.

Despite her parents' reservations, she landed a week's trial at the Northern Garage in Perth. It was quite a sight to see the goddaughter of Queen Victoria dressed in overalls, scraping oil and grease from gearboxes. At the end of the week, she was offered an apprenticeship for the princely sum of three shillings a week.

Three times a week, she studied maths and engineering with a tutor from Dundee Technical College.

Work at the garage was hard, backbreaking and could be dangerous. One of the worst accidents left her nursing a broken collarbone and ribs after she was crushed by a ten-ton lorry when it slipped as she worked underneath it.

YET she was determined to succeed and eventually moved to Dundee, working in the Caledon Ship Works, as the only woman among 3,000 men. Her workmates gradually got used to the idea of having a woman working with them and, in 1920, she finished her apprenticeship, top of her group.

It took another two years before she would achieve her dream of going to sea, when she was offered the post of tenth engineer with the Blue Funnel Line, sailing from Glasgow to Australia for [pounds sterling]10 a month. In her memoirs, she describes the 'thrill' of being measured for her first uniform, with the shiny gilt buttons, epaulettes and company badge on the cap.

Before she left, her father told her: 'A good voyage, Vicky. Write home from every port and go to church when you can. You have been brought up to know what is right, so do it.'

Hours were spent in the engine room, amid the hiss and roar of the boilers and the overpowering stench of thick, sulphur-smelling steam. In a man's world, there was no place for femininity. Her hair was cut short and her fingernails were more often than not caked black with grime.

Despite the toil - often working from 7am to 5pm, seven days a week - and the grim, cramped conditions during four months at sea, she loved it. In all, she made four voyages on the Australian run with the SS Anchises and one to China.

She was in Singapore in June 1924 when a telegram arrived, breaking the news that her father had died of pneumonia. The message ended: 'He was so proud of you.' On the Anchises, Miss Drummond had struck up an affectionate friendship with her second engineer, whom she refers to in her diary formally as Mr Quayle. On board, however, they gave each other nicknames. She called him Hedgehog, because of his sometimes prickly manner, and he called her Kate, because of her shrewish manner.

Her diary leaves little doubt that she was in love with him. When their last voyage came to an end, she was distraught at the thought of never seeing him again.

|

| SS Anchises (State Library of New South Wales) |

'Although we came from different backgrounds, our minds were perfectly attuned: we loved birds, the sea, engines and the British Empire. We shared the same wry sense of humour, the same love of travel. If there had been no Mrs Quayle, it is possible our relationship would have ripened into romance.'

She and Mr Quayle continued to correspond, on different ships and often on the other side of the world. She was at sea when she heard her beloved Hedgehog had died from pneumonia on the way to Cape Town in April 1927.

THE news left her devastated: 'I could not believe I would never see him again. It just knocked the bottom out of things for me and my whole career felt like a collapsing pack of cards. Everything in the engines reminded me of him, every tool, every job, it was almost more than I could stick.' She would never marry or have children. Determined to get on, she sat the second engineer's qualification and passed at the third attempt. By her next sailing, on the TSS Mulbera to East Africa, she had worked her way up to fifth engineer.

Yet, despite taking the chief engineer's exam 37 times, she failed each time and became convinced it was because of her sex: 'They would not pass me because I was a woman.' When war broke out in 1939, she fought against prejudice: 'No one would have me. They might be short-staffed, but that was no reason to employ a woman engineer. And certainly not in wartime.'

Eventually, she had to sign on as second engineer with a small international ship, sailing under a foreign flag. In wartime, crossing the seas was a perilous business with minefields, torpedo attacks and the constant threat of the German Luftwaffe.

She describes one particularly fierce night of bombardment, with gunfire and mines exploding all around: 'The ship was in a complete blackout and every now and then there would be a fantastic bang, which shook the whole ship. I kept thinking, "The next one will be us."' On one run, taking refugees from Gibraltar to Casablanca, she stood on deck and watched a ship sink in two minutes after striking a mine in front of them.

While she would earn the respect of her men, the British naval establishment-found it harder to accept her. On one Navy inspection, she wrote of how the officers saw her and 'looked amazed and disgusted.

I could almost hear them thinking: "Fancy having a woman Second, you can see it's a foreign ship." I was rather amused.' On August 25, 1940, after leaving Cornwall on the SS Bonita, the ship came under attack from a German bomber. Below deck, it was down to Miss Drummond to keep the engines going.

She would recall: 'I realised our only hope of survival was to dodge the bombs, so I gave her all the speed she could. I counted eight separate bursts of firing from the guns and bombs. All the lagging came off the pipes and fell like snow.

The feeling was as if the ship were lifted up and dropped each time.

'With the bombs, the machinegun fire and the engines of the plane, the noise was terrific. Flying debris hit the main water service pipe to the main engine and scalding water began to gush out. I had my ears stuffed with cotton wool to deaden the noise. There were no captain's orders. We were on our own.' Ordering her men to leave to safety, she remained alone in the engine room: 'The engine was a hissing, bubbling inferno and everything that could shake or bang rattled like marbles in a drum. The ship must be doomed.

I knew that now.

MY duty was to keep the engines going as long as they would turn. Was this the end, I wondered, banged and buffeted in the inferno of noise and steam?

It didn't seem a good way to go.' Through sheer determination, she managed to coax 12.5 knots out of the engines, a speed never before recorded in all the ship's 18 years.

Her efforts undoubtedly saved the ship and crew. Back on dry land, the brave engineer was met by journalists and cheering crowds. The ship's mate would describe her as 'about the most courageous woman I ever saw'.

After the war, Miss Drummond was on the first ship into Kiel and escorted the German prize ships over to the Forth. Bursting with pride, she wore her full Merchant Navy uniform in the Victory Parade. Of her two honours, she said: 'I was immensely proud of both my medals. They reassured me that at least someone believed my work was worthwhile.' She would continue sailing into her early 60s - taking her henna shampoo on every voyage to maintain her hair colour. And in 1959 she went through the Suez Canal as chief engineer, having at last attained the rank she had wished for all her life.

Her last voyage was in 1962 to Hong Kong. In later life, the highlight of her year was going to the Institute of Marine Engineers in London for their annual meetings.

Few knew the identity of the old lady at the back, listening avidly to all the lectures. She would have been thrilled to know the institute would later name a Victoria Drummond Room in her honour.

Her last six years were spent at a rest home in Kent. Gradually, she became more and more frail and stopped telling the stories of her time at sea. She died on Christmas Day, 1980 [sic], aged 86, leaving her unfinished memoirs. Her niece, Baroness Strange, would turn them into a book about her aunt.

Baroness Strange, who saw her aunt a week before she died, wrote: 'Victoria Drummond was finally Finished with Engines. Or perhaps as her spirit left the land and floated out to the open sea, she was at last Full Away.'

KATE GINN

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2006 Solo Syndication Limited. The Daily Mail.

Labels:

Female Marine Engineer,

Victoria Drummond

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Asking the right questions

On a recent visit to the Royal Dockyard Museum at Chatham, I read the intriguing story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta (Davies), a West African princess brought to England as a "gift" for Queen Victoria. Some sources state that Sarah was a goddaughter of the Queen as was her own daughter, Victoria Davies (Randle).

Sarah's extraordinary life is fully covered in this Youtube interview with Claire Kittings, Learning Manager at the National Portrait Gallery, but I'm now on the hunt for more stories about the Queen's numerous godchildren, especially those with unusual backgrounds. Who were they, and what happened to them?

A Wikipedia list can be found here, from which it is soon apparent most of these people came from the privileged upper echelons of British or European society (with the notable exception of Prince Albert Kamehameha of Hawaii) and does not include any godchildren from the middle or lower orders, or people of "colour" who came from the Empire like Sarah and her daughter, Victoria.

For example, the children of Maharajah Duleep Singh are not shown, neither is the Maori, Albert Victor Pomare. Could there be others? If anyone reading this knows, I'd love to hear from you.

One goddaughter who will be the subject of a future post is Victoria Drummond, the first female qualified Marine Engineer.

In the meantime, my quest continues. As Claire Kittings says in the interview, finding hidden history is all about asking the right questions.

Sarah was the subject of a book by Walter Dean Myers entitled At Her Majesty's Request: An African Princess in Victorian England

Sarah was the subject of a book by Walter Dean Myers entitled At Her Majesty's Request: An African Princess in Victorian England

Some links:

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

Victoria Davies

Duleep Singh

|

| The "Dahomian Captive" |

Sarah's extraordinary life is fully covered in this Youtube interview with Claire Kittings, Learning Manager at the National Portrait Gallery, but I'm now on the hunt for more stories about the Queen's numerous godchildren, especially those with unusual backgrounds. Who were they, and what happened to them?

A Wikipedia list can be found here, from which it is soon apparent most of these people came from the privileged upper echelons of British or European society (with the notable exception of Prince Albert Kamehameha of Hawaii) and does not include any godchildren from the middle or lower orders, or people of "colour" who came from the Empire like Sarah and her daughter, Victoria.

For example, the children of Maharajah Duleep Singh are not shown, neither is the Maori, Albert Victor Pomare. Could there be others? If anyone reading this knows, I'd love to hear from you.

One goddaughter who will be the subject of a future post is Victoria Drummond, the first female qualified Marine Engineer.

In the meantime, my quest continues. As Claire Kittings says in the interview, finding hidden history is all about asking the right questions.

Some links:

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

Victoria Davies

Duleep Singh

Monday, August 8, 2011

Vale White Mouse - Bravest of the Brave

Nancy Wake has just died aged 98. Words are superfluous. The actions of this extraordinary woman are her legacy to history. For sixty years, Australia disgracefully refused to recognise her wartime achievements and only in 2004 was she finally accorded her birth nation's highest honour.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nancy_Wake

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nancy_Wake

|

| "The White Mouse", Portrait by Robert Hannaford |

Monday, July 18, 2011

The Lady and the Pirates

While researching an unrelated topic in an online historical newspaper, I happened upon mention of a book with the florid title of A Lady's Captivity among Chinese Pirates in the Chinese Seas and I was swiftly diverted.

Who was this "lady" and how did she come to be in the "Chinese Seas" in the first place?

Note: Assuming this has to be the same Captain Matthew Rooney, he was already a major player in the "Chinese Seas" himself and is worthy of having a biography of his own. Dealing in everything from opium to camphor, he is mentioned in various histories about Formosa (Taiwan).

Some details can be read here.

Who was this "lady" and how did she come to be in the "Chinese Seas" in the first place?

| Fanny Loviot |

It turns out she was a Frenchwoman, Fanny Loviot, who travelled from France to San Francisco in the rip-roaring days of the California Gold Rush. She was rather reticent in describing what she was actually up to but given her destination, it is more than likely that the "commercial" interests she mentions were the prostitution business. She later decided to travel to Hong Kong and it was while returning from there that she became the victim of pirates and the subject of a major rescue effort by the British.

The full text of A Lady's Captivity ... is freely available to read online in a number of formats and even if some of the facts as related therein are as shady as Fanny's background, the voyage on the Chilean-registered brig Caldera in the company of the dashing Captain Matthew Rooney [see note below] and the Chinese merchant Than Sing whose actions saved Fanny from a desperate fate, still makes for an exciting read even today. The book was also reprinted recently by the National Maritime Museum in the UK.

On her return to France, Fanny gained much publicity and naturally enough published the account of her adventures. It was later translated into English by the equally fascinating and adventurous novelist, traveller, and Egyptologist, Amelia B. Edwards.

However, I have been unable to discover what happened to Fanny in later life and she seems to have faded from the public eye.

Another French Wikipedia entry describes the French lottery scheme under which Fanny purportedly travelled to California. This turns out to be an amazing historical scam in itself and Curt Gentry's 1964 book The Madams of San Francisco devotes an entire chapter to the scheme. It had various aims, primarily to fill government coffers and ensure the return of Louis Napoleon to power but was also a way of getting rid of many hundreds of French poor and undesirables by packing them off to California. Even the public drawing of the tickets in the Champs Elysees in November 1851 with 40,000 people looking on seems to have been conducted with sleight of hand and none of the citizens taken in by the scam ever received a penny.

| See Chapter 5 "The Lottery of the Golden Ingots" |

Some details can be read here.

Friday, July 8, 2011

Correction!

This is a correction to an earlier post I wrote on female despatch riders.

Various experts (including Barbara Legrand a WW1 battflefield guide) have stated on the Facebook page for the Lost Diggers of World War I that this woman is most likely a French mademoiselle dressing up for fun by wearing a corporal's uniform and cap and she isn't a despatch rider herself.

It just goes to show how images and photographs can be misinterpeted, especially if one doesn't examine them closely enough or isn't an expert in the era!

This is not to say there were no female despatch riders at all during First World War, and women riders most certainly played a very important role in the Second.

The Wrens were among the first.

http://www.seayourhistory.org.uk/content/view/133/221/1/1/

See also:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/tees/hi/people_and_places/history/newsid_8531000/8531137.stm

Various experts (including Barbara Legrand a WW1 battflefield guide) have stated on the Facebook page for the Lost Diggers of World War I that this woman is most likely a French mademoiselle dressing up for fun by wearing a corporal's uniform and cap and she isn't a despatch rider herself.

It just goes to show how images and photographs can be misinterpeted, especially if one doesn't examine them closely enough or isn't an expert in the era!

This is not to say there were no female despatch riders at all during First World War, and women riders most certainly played a very important role in the Second.

The Wrens were among the first.

http://www.seayourhistory.org.uk/content/view/133/221/1/1/

See also:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/tees/hi/people_and_places/history/newsid_8531000/8531137.stm

Saturday, June 18, 2011

"A lady of an excellent spirit and judgment ..."

| Elizabeth Claypole, The Royal Collection |

Elizabeth Claypole is one such example. The short entry on the Westminster Abbey website where she is buried intrigued me and I tried to find out more about her but with little success.

It seems that no-one has attempted a biography - there isn't even an historical novel - about Elizabeth's interesting, if short, life. She has walk-on roles in a few books about her father Oliver Cromwell, but the only detailed articles I could find on her were written by men in the 19th Century and it is odd that she does not seem worthy of more recent scholarship.

Too often, the truth of history is altered or re-written to suit changing times, and when King Charles II was restored to the English throne he was determined to blacken the reputations of everyone who had been responsible for the execution of his father, King Charles I, or had been supporters of Oliver Cromwell. Many individuals (including Cromwell himself) who had originally been buried at Westminster Abbey were exhumed, hung at Tyburn and the bodies eventually ended up in a communal pit in the churchyard of St Margaret's next door and only Elizabeth Claypole remained where she was. Perhaps she was simply overlooked or, more likely, she was still remembered as someone who tried to intercede with her father on behalf of royalist offenders and others; that she was the only person who had the power to move him. It was said that she even berated him on her deathbed for the blood he had caused to be shed.

| John Claypole, National Portrait Gallery |

In the two most reproduced portraits of Elizabeth - one of which is this rather haughty one at Chequers - and another in the National Portrait Gallery she is shown dressed in silken and expensive finery that would have been anathema to her Puritan father. As both portraits were completed after her death one can't help but wonder if there was deliberate embellishment and/or manipulation of her image for political purposes, as she seems quite different from the fresher faced and simpler miniatures in the Royal Collection and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

| Elizabeth Claypole, Victoria and Albert Museum |

It was well-known that Oliver Cromwell was often at loggerheads with his strong-willed daughter and despaired of her fondness of what he perceived to be "worldly vanities and worldy company". But in spite of his frustrations with her, it seems that Elizabeth was always his favourite child and he was utterly devastated when she died at Hampton Court at the age of just 29. Perhaps her loss was too much to bear and he himself died just one month later.

‘a lady of an excellent spirit and judgment, and of a most noble disposition, eminent in all princely qualities conjoined with sincere resentments of true religion and piety’

(Mercurius Politicus, 5–12 Aug 1658).

Among the portraits in the National Portrait Gallery collection is this mid-19th Century engraving of Cromwell's family pleading with him to spare the life of King Charles I. Presumably the woman leaning on his arm is Elizabeth.

For more details on the life of Elizabeth Claypole, see English Historical Review R. W. Ramsay 1892 and Memorable Women of Puritan Times Vol 1 James Anderson 1862, also the Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

Saturday, May 28, 2011

"An extraordinary girl; she never would sit still."

In a week when I'm baffled by the reasoning (if any) behind the idiocy of "planking" or what young women hope to achieve in demanding the right to dress and look like hookers on "slut walks", it was heartening to stumble across the remarkable story of a woman from an earlier generation who deliberately went into a hazardous and remote area of the world populated by headhunters - the traditional kind, not modern-day business ones! - but who was accepted by the people and developed a very close bond with them.

She was not formally trained in anthropology but she was awarded the Lawrence of Arabia Medal for her work among the Nagas. (See here for general information on Nagaland.)

Later, in true Empire spirit, Ursula Graham Bower (Betts) displayed grit, resourcefulness and courage in a little-known arena of the Second World War, leading her Naga people in guerilla warfare against the Japanese.

Annabel Venning gives a good summary of her life in this 2010 article in The Daily Mail. In 1945, Time Magazine wrote about her exploits with the lurid title of "Ursula and the Naked Nagas".

Yet again, this is another amazing woman who deserves to be much better known but still seems to be just another feminine footnote to history.

Maybe that could change, with a new book on Ursula scheduled to be published in 2012.

Ursula wrote several books herself and a couple of radio plays were written about her exploits. She took vast numbers of photographs, including those in this collection.

Ursula wrote several books herself and a couple of radio plays were written about her exploits. She took vast numbers of photographs, including those in this collection.

She was not formally trained in anthropology but she was awarded the Lawrence of Arabia Medal for her work among the Nagas. (See here for general information on Nagaland.)

Later, in true Empire spirit, Ursula Graham Bower (Betts) displayed grit, resourcefulness and courage in a little-known arena of the Second World War, leading her Naga people in guerilla warfare against the Japanese.

Annabel Venning gives a good summary of her life in this 2010 article in The Daily Mail. In 1945, Time Magazine wrote about her exploits with the lurid title of "Ursula and the Naked Nagas".

Yet again, this is another amazing woman who deserves to be much better known but still seems to be just another feminine footnote to history.

Maybe that could change, with a new book on Ursula scheduled to be published in 2012.

Ursula wrote several books herself and a couple of radio plays were written about her exploits. She took vast numbers of photographs, including those in this collection.

Ursula wrote several books herself and a couple of radio plays were written about her exploits. She took vast numbers of photographs, including those in this collection.

Others can be found along with diaries, manuscripts and other documents at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and at Cambridge University, including some unique colour film footage from the 1930s and 1940s.

For anyone wanting to gain more insight into what women of that British Empire era could be like, the two-part video interview done in 1985 by Alan Macfarlane is an excellent resource.

In the first part, Ursula describes her immediate feeling of connection with the Naga people, as if she had always known them. Her manner is very matter of fact as she describes living among them, their culture and habits and, not least, their great bravery during the War. And in the last few minutes on the second tape, she tells us in her wonderfully plummy voice, and with typical understatement, how she came to meet her husband, get engaged and married within three weeks! It seems she made the right choice and F. N. Betts had a distinguished career of his own and wrote many publications relating to natural history. One of their daughters described going back to Nagaland many years later in this transcript of a BBC radio interview.

Her mother once said Ursula was "an extraordinary girl; she never would sit still," but it seems she did sit still long enough to have this oil painting done wearing the traditional wedding dress of the Zemi people. The portrait is from a private collection and can be found among the numerous artefacts listed on the university Index relating to Ursula.

Labels:

F N Betts,

Naga Queen,

Ursula Betts,

Ursula Graham Bower

Saturday, May 7, 2011

The hazards of compilations

I recently picked up a copy of a 1997 book entitled The Giant Book of Influential Women: The 100 Greatest Women of All Time by Deborah G. Felder. (Not to be confused with a recent work of the same name edited by Kathleen Kuiper and published by Britannica - available to read here on Scribd.)

I am always curious as to how an author or editor decides who is to be included in such books and, to be honest, why they get published in the first place as they usually end up in huge wobbly piles in remainder bookshops. They must be fairly easy to write but are not always reliable works as they are often derivative or cobbled together from secondary or previously published sources and some of them are guilty of perpetuating myths or inaccuracies.

While I concur with some of Felder's choices in this particular work - those women who have left important marks on history that still resonate around the world such as Florence Nightingale, Marie Curie, or Emmeline Pankhurst - others left me baffled. As a non-American, they are unfamiliar to me: civil rights activists, psychologists and short story writers.

The author did admit in her introduction that the project was bound to generate controversy. She gathered her names from a survey of women's studies professors in American colleges or universities, which seems very narrow as surely their reasoning was bound to get skewed in the direction of their academic (American) interests? One who declined to submit a list wrote: "Frankly, I think your project is misguided and will lead to more criticism than you can imagine." I'm guessing it did as I notice the book has gone into subsequent editions in which the title has wisely been changed to 100 American Women who Shaped American History.

In 2010, the British newspaper The Independent published a similar list. Again, if one is unfamiliar with modern British entertainment, politics or sport, the majority of these names mean nothing. These women might have changed Britain recently, but not necessarily impacted on the world as a whole. You can read that list here.

Other selections can be highly subjective and even verge on the ridiculous, such as an Esquire magazine list of 2010 in which serious contenders like Joanne of Arc and Golda Meir have to compete against B-grade actresses, pop princesses and even the 1972 Dallas Cheerleaders!

One could spend many hours trying to find a definitive list of women who changed the world, but it would be impossible as of course no two people are going to come to the same conclusions. Much better to narrow down your search to specific eras or endeavours: top women athletes, scientists, reformers, etc. I notice there is even a book out there on the 100 greatest Welsh women!

Surprisingly, two books on wild/notorious women have been published already this year in Australia that appear to go over tired ground. In this day of quick look-ups on Google and Wikipedia for anyone who wants a pocket history of an individual, I don't understand the reasoning by publishers as both books are rather expensive and will end up in those wobbly remainders piles sooner than later.

Wild Women by Pamela Robson includes individuals who have been written about extensively already like Bonnie Parker (Bonnie & Clyde) and the female pirate Anne Bonny but at least she does seem to offer some hope by including intriguing lesser-known characters such as a Queen of Angola.

Notorious Australian Women by Kay Saunders tackles well-worn women like Tilly Devine and Mary Bryant who have been covered in numerous compilations on infamous Australians.

And being the author of a major work on Lola Montez myself, I must take umbrage with the ludicrous and historically ill-informed choice of cover on this second work!

Lola Montez could never be described as an "Australian woman" by any stretch of the imagination. She only visited Australia for a short period in the 1850s as a performer, albeit creating a great deal of notoriety when she did so.

Nobody in their right mind would dare to suggest that other famous entertainer, Frank Sinatra, was a notorious "Australian man" as a result of his visit to the country in 1974 during which he created a similar degree of mayhem! (Check out the Dennis Hopper movie about that event.)

I am always curious as to how an author or editor decides who is to be included in such books and, to be honest, why they get published in the first place as they usually end up in huge wobbly piles in remainder bookshops. They must be fairly easy to write but are not always reliable works as they are often derivative or cobbled together from secondary or previously published sources and some of them are guilty of perpetuating myths or inaccuracies.

While I concur with some of Felder's choices in this particular work - those women who have left important marks on history that still resonate around the world such as Florence Nightingale, Marie Curie, or Emmeline Pankhurst - others left me baffled. As a non-American, they are unfamiliar to me: civil rights activists, psychologists and short story writers.

The author did admit in her introduction that the project was bound to generate controversy. She gathered her names from a survey of women's studies professors in American colleges or universities, which seems very narrow as surely their reasoning was bound to get skewed in the direction of their academic (American) interests? One who declined to submit a list wrote: "Frankly, I think your project is misguided and will lead to more criticism than you can imagine." I'm guessing it did as I notice the book has gone into subsequent editions in which the title has wisely been changed to 100 American Women who Shaped American History.

|

| 1997 Australian Edition |

|

| 2005 American (Bluewood) Edition |

Other selections can be highly subjective and even verge on the ridiculous, such as an Esquire magazine list of 2010 in which serious contenders like Joanne of Arc and Golda Meir have to compete against B-grade actresses, pop princesses and even the 1972 Dallas Cheerleaders!

One could spend many hours trying to find a definitive list of women who changed the world, but it would be impossible as of course no two people are going to come to the same conclusions. Much better to narrow down your search to specific eras or endeavours: top women athletes, scientists, reformers, etc. I notice there is even a book out there on the 100 greatest Welsh women!

Surprisingly, two books on wild/notorious women have been published already this year in Australia that appear to go over tired ground. In this day of quick look-ups on Google and Wikipedia for anyone who wants a pocket history of an individual, I don't understand the reasoning by publishers as both books are rather expensive and will end up in those wobbly remainders piles sooner than later.

Wild Women by Pamela Robson includes individuals who have been written about extensively already like Bonnie Parker (Bonnie & Clyde) and the female pirate Anne Bonny but at least she does seem to offer some hope by including intriguing lesser-known characters such as a Queen of Angola.

Notorious Australian Women by Kay Saunders tackles well-worn women like Tilly Devine and Mary Bryant who have been covered in numerous compilations on infamous Australians.

And being the author of a major work on Lola Montez myself, I must take umbrage with the ludicrous and historically ill-informed choice of cover on this second work!

Lola Montez could never be described as an "Australian woman" by any stretch of the imagination. She only visited Australia for a short period in the 1850s as a performer, albeit creating a great deal of notoriety when she did so.

Nobody in their right mind would dare to suggest that other famous entertainer, Frank Sinatra, was a notorious "Australian man" as a result of his visit to the country in 1974 during which he created a similar degree of mayhem! (Check out the Dennis Hopper movie about that event.)

Thursday, May 5, 2011

The last one standing (or sitting) is a woman

A poignant day in history: the last man believed to have served in World War I has died in Perth, Western Australia. He was Claude Choules, and despite the French-sounding name was British.

That leaves Florence Green, who served as a waitress in the fledgling Royal Air Force in 1918 as the last (wo)man standing, or perhaps more often sitting, given her great age.

However, this isn't to say that there aren't still a few longlived stray individuals out there who might also qualify to have served in some capacity in the Great War.

What about the many other nationalities who are often overlooked in these mostly Western statistics?

According to some sources in the British army alone, over 1.5 million "Indians and other 'coloured' troops" served in that war and yet there is very little known about most of them. Plus there are the non-combatant labourers such as the Chinese and Africans who did not fight, but also died in the course of doing their work. No doubt some of them might also have been waiters like Florence Green, but because of the class and racial attitudes of the day, they have long been lost to history.

|

| Florence celebrates her 110th in February (pic British Forces News) |

However, this isn't to say that there aren't still a few longlived stray individuals out there who might also qualify to have served in some capacity in the Great War.

What about the many other nationalities who are often overlooked in these mostly Western statistics?

According to some sources in the British army alone, over 1.5 million "Indians and other 'coloured' troops" served in that war and yet there is very little known about most of them. Plus there are the non-combatant labourers such as the Chinese and Africans who did not fight, but also died in the course of doing their work. No doubt some of them might also have been waiters like Florence Green, but because of the class and racial attitudes of the day, they have long been lost to history.

|

| Waitresses wanted |

Labels:

Claude Choules,

Florence Green,

Last World War l veteran,

WRAF

Saturday, March 19, 2011

"And her ghost may be heard as you pass by that billabong ..."

If you were to ask the average person what they know about the Australian woman, Christina Rutherford Macpherson, most likely you will be met with a blank stare or - at best in this day and age - "Is that the real name of Elle Macpherson?" - ie the fashion model.

Christina has an unkind fame that has been obscured by varying degrees of hysteria and legend and, not least, the self-importance of others, from hack journalists to radical unionists and from music theorists to academic historians. My attempt to find out more about her has been both intriguing and frustrating.

Christina Macpherson was buried in Melbourne's St Kilda Cemetery in 1936 and her grave remained unmarked until the mid-1980s when a TV documentary team rediscovered it and a niece of hers arranged for this plaque to be placed on her grave.

Waltzing Matilda is one of the world's most recognisable songs, and there have been numerous theories, debate and controversy about its real origins. There is no doubt that Christina was connected with its first outing - using an autoharp she played the first sketchy score to the poet A B (Banjo) Paterson to which he penned the words. That first score has now become a National Treasure, even if it is obvious that the original melody Craigilea bears little resemblance (at least to my non-muscial ear) to the Waltzing Matilda now known world-wide, with this latter being apparently the invention of Marie Cowan although that, too, has its origins elsewhere in British folk tunes. Marie's name usually appears on all sheet music as the composer and/or arranger of that version. To complicate matters further, there is another version called the "Queensland", as sung here by The Seekers.

For anyone wishing to read more, the National Library of Australia has a complete web section devoted to the history of Waltzing Matilda and its myths. The website of Roger Clarke also dazzles and confounds with even more information.

There is no intention of adding to the fantasies or theories in this blog as it is the woman Christina Macpherson herself who interests me and is a prime example of late 19th Century fifteen minutes of fame factor.

What else did she do in life apart from crying at an opportune moment as a baby resulting in the shooting of the notorious bushranger Mad Dog Morgan and later scribbling down a tune for a visiting journalist? See her brief biography in this Friends of St Kilda Cemetery newsletter.

Obviously, she never married. Did she remain an isolated spinster and pine away, still carrying a torch for Banjo Paterson - as some have suggested? Or did she busy herself with the usual charity and family care duties that was the fate of so many single women from that era? In the Australian Electoral Roll between 1914 and 1933, she was simply listed as "home duties, F [female]" which suggests she didn't do much at all and probably had a small private family income.

Newspapers of the era are mostly silent on her (apart from Waltzing Matilda connections) and just about the only record of her in a personal way is a brief mention of her death in the Wills and Estates column of The Age in June 1936 in which she was described as a spinster who lived in Avoca Street, South Yarra, and who left the sum of £3,624 to her sister, who is unamed but is probably the Lady McArthur who found among her effects the letters that passed between Christina and Banjo Paterson relating to Waltzing Matilda (Melbourne Sun, 14 April 1941) and thus confirming her connection to the music.

Rather surprisingly, neither Christina Macpherson nor Marie Cowan rates her own entry in the online Australian Dictionary of Biography. It is even more disappointing that they are not considered noteworthy for entry in the Australian Women's Register or the Australian Women's History forum either.

As can be see from searching the Music Australia archive, Marie Cowan (died 1919) is linked to numerous versions and possibly other music compositions, but her biographical details are even more sketchy than those of Christina and there does not seem to be any accessible image of her.

Is the music to Australia's "unofficial national anthem" less important than Banjo's famous words?

When one considers how much of Australia and its history, both at home and abroad through two World Wars and all subsequent ones, as well as its national pride, culture and identity have been associated with the melody/melodies of Waltzing Matilda, it would be fitting if the women who were involved in its creation are given greater recognition for their contributions!

It is ironic also that the murky history of Waltzing Matilda continues to this day and despite its creator/s being dead for more than the requisite 50 years, it seems that copyright still belongs to the Americans and thus Australians are unable to play it professionally without first obtaining permission from the copyright holder in the United States to do so.

|

| Christina Macpherson c. 1900. National Library of Australia |

Christina Macpherson was buried in Melbourne's St Kilda Cemetery in 1936 and her grave remained unmarked until the mid-1980s when a TV documentary team rediscovered it and a niece of hers arranged for this plaque to be placed on her grave.

|

| Image: Iain Macfarlane. www.find-a-grave.com |

For anyone wishing to read more, the National Library of Australia has a complete web section devoted to the history of Waltzing Matilda and its myths. The website of Roger Clarke also dazzles and confounds with even more information.

There is no intention of adding to the fantasies or theories in this blog as it is the woman Christina Macpherson herself who interests me and is a prime example of late 19th Century fifteen minutes of fame factor.

What else did she do in life apart from crying at an opportune moment as a baby resulting in the shooting of the notorious bushranger Mad Dog Morgan and later scribbling down a tune for a visiting journalist? See her brief biography in this Friends of St Kilda Cemetery newsletter.

Obviously, she never married. Did she remain an isolated spinster and pine away, still carrying a torch for Banjo Paterson - as some have suggested? Or did she busy herself with the usual charity and family care duties that was the fate of so many single women from that era? In the Australian Electoral Roll between 1914 and 1933, she was simply listed as "home duties, F [female]" which suggests she didn't do much at all and probably had a small private family income.

Newspapers of the era are mostly silent on her (apart from Waltzing Matilda connections) and just about the only record of her in a personal way is a brief mention of her death in the Wills and Estates column of The Age in June 1936 in which she was described as a spinster who lived in Avoca Street, South Yarra, and who left the sum of £3,624 to her sister, who is unamed but is probably the Lady McArthur who found among her effects the letters that passed between Christina and Banjo Paterson relating to Waltzing Matilda (Melbourne Sun, 14 April 1941) and thus confirming her connection to the music.

Rather surprisingly, neither Christina Macpherson nor Marie Cowan rates her own entry in the online Australian Dictionary of Biography. It is even more disappointing that they are not considered noteworthy for entry in the Australian Women's Register or the Australian Women's History forum either.

As can be see from searching the Music Australia archive, Marie Cowan (died 1919) is linked to numerous versions and possibly other music compositions, but her biographical details are even more sketchy than those of Christina and there does not seem to be any accessible image of her.

Is the music to Australia's "unofficial national anthem" less important than Banjo's famous words?

When one considers how much of Australia and its history, both at home and abroad through two World Wars and all subsequent ones, as well as its national pride, culture and identity have been associated with the melody/melodies of Waltzing Matilda, it would be fitting if the women who were involved in its creation are given greater recognition for their contributions!

It is ironic also that the murky history of Waltzing Matilda continues to this day and despite its creator/s being dead for more than the requisite 50 years, it seems that copyright still belongs to the Americans and thus Australians are unable to play it professionally without first obtaining permission from the copyright holder in the United States to do so.

|

| Image: National Library of Australia |

Saturday, March 5, 2011

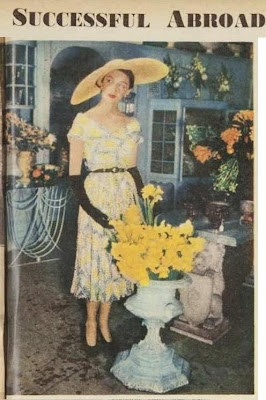

Flower Power

It is interesting how the names of some women that were once well-known and lauded in the media for their design and domestic advice have almost disappeared from the lexicon.

Julia Child has had a revival, thanks largely to a recent blog that became a film. Likewise Elizabeth David had a bit of a comeback with new biographies and a telemovie. And despite earlier disgrace, Martha Stewart still manages to hold her own as the domestic guru on craft and interior design as well as the kitchen.

Modern women may be baffled by how much store was once set on the art of flower arranging for the home. Today, no-one would think twice about making up a decorative arrangement that mixes flowers with bits of fruit, grasses, pine cones or feathers, but there was a time when it was frowned upon and considered to be “avant garde” and it was Constance Spry who was instrumental in bringing about that change.

Spry was the Martha Stewart of her day and although she was considered primarily a society florist, she was much more than that.

In the 1950s, no conscientious housewife would have been without her recipe book, The Constance Spry Cookery Book which is intermittently in print (latest edition 2004).

Another photo, also from the AWW dated 13 May 1950, shows the Sydney model Judy Barraclough choosing flowers at one of her “favourite London haunts” - Spry’s shop.

Before dismissing Spry as outdated and inconsequential in this day and age, it is worth considering what she achieved for herself in what was an era of great transition for many women.

In a review of her latest biography by Sue Shepherd, Robert O’Byrne in The Irish Times shows an insight into Spry that has been overlooked.

Julia Child has had a revival, thanks largely to a recent blog that became a film. Likewise Elizabeth David had a bit of a comeback with new biographies and a telemovie. And despite earlier disgrace, Martha Stewart still manages to hold her own as the domestic guru on craft and interior design as well as the kitchen.

Modern women may be baffled by how much store was once set on the art of flower arranging for the home. Today, no-one would think twice about making up a decorative arrangement that mixes flowers with bits of fruit, grasses, pine cones or feathers, but there was a time when it was frowned upon and considered to be “avant garde” and it was Constance Spry who was instrumental in bringing about that change.

Spry was the Martha Stewart of her day and although she was considered primarily a society florist, she was much more than that.

|

| The Windsors 1937 (AP image) |

Her most famous early project was probably the design of the flowers for the wedding at Chateau de Cande of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in 1937 - not a good social move by Spry, given those circumstances - but her status was restored by the time of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth ten years later and the subsequent 1953 Coronation for which Spry designed the flowers in Westminster Abbey, the celebratory dinners and along the processional route. She also often designed arrangements for operas and ballets at Covent Garden.

Spry also ran schools (including the forerunner of the Cordon Bleu School) and gave advice on gardening during war-time when flowers were pulled up in favour of vegetables. But some of her ideas still seem rather outlandish - how many modern brides would consider parsley or cabbage leaves in their bouquets - as was fashionable in the 1930s?

Women living in the British Dominions and Colonies in an era when the mother country England was still treated with deference and awe seemed to be particularly fascinated by Spry and would follow her advice and suggestions slavishly. In certain circles, sending one’s daughter overseas to England to be “finished” at the Constance Spry school was a highly prestigious aspiration.

It is hard to imagine what - apart from flower arranging, deportment, and knowing not to eat peas off your knife - the girls were expected to achieve. Some of these establishments were also called “charm” schools and basically existed to teach frumps how to become sophisticated and cultured (e.g. how to read a French menu and wield a cigarette holder with aplomb) and thereby snag a rich husband.

Research of Australian magazines and newspapers of the day (see TROVE) show numerous reports gushing over the latest Constance Spry publications and endless society column boasts about the lucky ladies about to sail to, or just returned from, study at Spry’s school.

This photo from The Australian Women’s Weekly, 23 March 1955 shows a group of society types at a fashion event in London and in which Australian-born Mrs Vyvyan Holland (her husband was the son of Oscar Wilde) is frightfully game to wear a hat of “real white lilac” made by Constance Spry. We trust there were no bees about!Before dismissing Spry as outdated and inconsequential in this day and age, it is worth considering what she achieved for herself in what was an era of great transition for many women.

In a review of her latest biography by Sue Shepherd, Robert O’Byrne in The Irish Times shows an insight into Spry that has been overlooked.

andSpry’s innovations within her field deserve to be acknowledged, but so too, and more importantly, does her position as a role model for women seeking to take control of their lives.

... But breaking free from the constraints of [her] upbringing, [she] had the foresight to recognise how a natural aptitude could be deployed to generate income and provide employment. Thanks to flower arranging, Spry gained global fame, publishing books and giving lecture tours around the world while running a school where other women could learn the skills that had proven so profitable for her.

In our celebrity-driven age when unkempt chefs compete with each other as to who has the foulest mouth and worst hygiene habits at the expense of the food, and manners and etiquette have become laughable or despised, maybe it would be refreshing to have the wheel turn back a little and a new Constance Spry bring back some elegance and style into our lives.

Click here for a rare Pathe newsreel of 1945 with some of Spry’s design tips.

This blog carries an extensive summary of her important contribution to flower design. And, as keen gardeners may know, Spry was instrumental in saving many rare flowers from extinction and there is a famous rose named after her.

Her 1960 obituary in The Illustrated London News was brief and succinct.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)